Editorial: Leveling the Solution Up to the Global Air Quality Problem

News

16th Nov 2017

The air we breathe is often a mystery, and every day we breath in a lot of it: about 10,000 liters or the volume of an average above-ground swimming pool. Except in very specific situations — such as near someone smoking, an old car fuming gases, or a heavily polluted or developing urban area (like New Delhi, where airlines recently halted flights) — many of us don’t think about the chemicals that enter our bodies on a daily basis. They remain an invisible and unnoticed threat.

Recently in Houston after Hurricane Harvey, my team and I saw firsthand just a glimpse of some of the things that can go wrong when toxic chemicals leach into our atmospheric environment — people coughing and having trouble breathing without knowing why. As illustrated by two new large health studies, however, air quality broadly influences public health around the world, not just in disaster-stricken areas.

Last month, the Lancet Commission on Pollution and Health released startling numbers:

Pollution is the largest environmental cause of disease and premature death in the world today. Diseases caused by pollution were responsible for an estimated 9 million premature deaths in 2015–16% of all deaths worldwide — three times more deaths than from AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria combined and 15 times more than from all wars and other forms of violence. In the most severely affected countries, pollution-related disease is responsible for more than one death in four.

The Commission noted that developed countries have made big strides in recent years but it is still an uphill battle for much of the world. The authors of the report concluded that pollution “threatens the continuing survival of human societies.”

With 92% of the world’s population living in areas with potentially dangerous air quality, according to the World Health Organization, the threat is pervasive. It even reaches us in our earliest phases of development: A study in JAMA Pediatrics last month details how prenatal exposure to particulate matter in the air affects fetuses in the womb. The study analyzed air pollution exposure in 641 pregnant mothers relative to the telomere length in the mothers’ newborn babies. Shortened telomeres are associated with disease and aging. They found:

Mothers who were exposed to higher levels of PM2.5 [particles with an aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm] gave birth to newborns with shorter telomere length. The observed telomere loss in newborns by prenatal air pollution exposure indicates less buffer for postnatal influences of factors decreasing telomere length during life. Therefore, improvements in air quality may promote molecular longevity from birth onward.

Interestingly, another study, just published in The Lancet Planetary Health, also linked particulate pollution to osteoporosis, suggesting that even a small increase in PM2.5 concentrations leads to an increase in bone fractures in older adults.

So air pollution is a pervasive, global health issue. What can we do to change that?

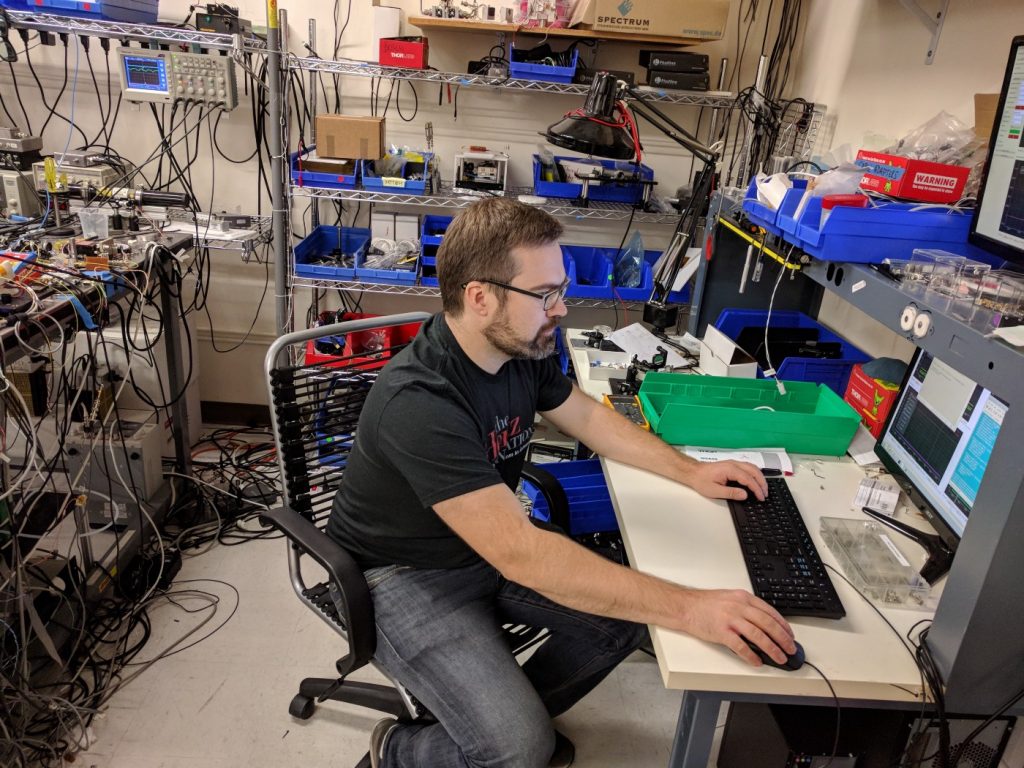

I come at this problem as a physicist, not a physician or even a chemist. I build sensors and have devoted my career to understanding quantum systems. Looking out at the range of wicked problems facing society, my team and I decided that air quality is one that we can help tackle through our sensor technology.

Our air quality work at Entanglement focuses on generating quantitative data — measuring chemicals in the environment down to extremely low concentrations to help inform communities and industries. We have used our AROMA instrument to map ambient benzene concentrations and to locate and identify hazardous concentrations of chemicals like trichloroethylene (TCE), a carcinogen that causes birth defects in very low concentrations.

An industrial chemical, TCE can leak into groundwater and then rise into indoor air spaces. In our own backyard, the San Francisco Bay area, we have observed elevated levels of TCE in six sanitary sewer systems due to contaminated groundwater leaking into the sanitary sewer. Early evidence shows that these levels are as hazardous as living on top of a TCE plume itself.

Having the ability to quickly quantify risks in the environment is an important step in combatting the global air pollution problem. The traditional method of collecting air quality data via stationary labs miles apart is no longer going to cut it. We need to level up to the magnitude of the problem — developing an arsenal of mobile sensors that policy-makers, companies, and other stakeholders can use to identify hazards and keep people out of harm’s way.

Tony Miller is the CEO and a co-founder of Entanglement Technologies.